Top Surgery and BMI

Why BMI Shouldn’t Decide Your Access to Care

When you are already dealing with dysphoria, being told your body is too big for top surgery can feel crushing. Some people are refused a consultation outright because of their BMI. Others are told they can only get surgery if they lose a certain amount of weight first, with no clear plan and no clear reason beyond a vague claim that it is safer. Delaying surgery for years while chasing a target weight can worsen anxiety, depression, and dysphoria, and can push people toward extreme dieting or disordered eating just to qualify for care.

BMI (Body Mass Index) is often treated as if it decides whether your body is allowed in the operating room. In reality, it is a rough formula based only on height and weight. It does not know anything about your actual health, your support system, or how badly you need surgery, and the research on top surgery and BMI is far more reassuring than many policies suggest. BMI is a blunt, flawed tool that should not be used as a strict cutoff for top surgery. The evidence supports offering chest masculinization to people across a wide range of body sizes, with a focus on individual risk, honest discussion of complications, and making surgery safer and more accessible for people of all BMIs.

On this page

What Is BMI?

I can't imagine a young queer person who is already uncomfortable in their body, thinking there is no way I can ever change this, because my BMI is too high.

Felix Vandergrift was denied even a consultation for top surgery because of his BMI. One number, calculated by a computer, closed the door before he could talk to a surgeon about his goals, his health, or his options.

Stories like this all come back to the same question: what is that number, really?

Body Mass Index, or BMI, is a simple formula that uses only height and weight to create a single number. That number is then sorted into categories like underweight, normal weight, overweight, or obese. BMI was designed in the 1800s to look at trends in large groups of people, not to decide whether any one person is healthy or ready for surgery.

BMI does not measure body fat directly. It does not look at where fat sits on the body, how much is fat versus muscle, or how someone actually lives day to day. Two people can have the same BMI and very different health, strength, and medical needs. BMI also does not account for things like age, race, gender identity, or how hormones affect the body over time.

Even with all of these limits, BMI is often treated as if it is a verdict on whether a body is safe to operate on. For top surgery, that means many people are judged first by a number, not by a full picture of their health or the benefits they could gain from surgery.

Why Surgeons and Facilities Still Use BMI

If BMI is such a rough tool, why is it sometimes used to determine top surgery eligibility?

Safety Concerns, Especially With Anesthesia

Higher BMI is often linked with other health issues, like sleep apnea, high blood pressure, or diabetes. Anesthesiologists worry about how safely they can keep someone breathing, protect their heart and lungs, and lower the chance of blood clots during and after surgery.

Some anesthesia departments set a BMI cutoff for outpatient surgery. That does not mean surgery is impossible, but it may mean they only want to do it in a hospital instead of a small surgery center, or only up to a certain BMI in that particular facility.

Equipment and Facility Limits

Operating rooms and recovery areas are built around certain weight limits and body sizes. This can include:

- How much weight the operating table can safely hold

- Whether they have lifting devices and positioning tools that work for larger bodies

- Whether gowns, blood pressure cuffs, and post op compression vests come in the right sizes

Some facilities use BMI as a rough stand in for these issues. Instead of investing in better equipment, they decide that anyone above a certain BMI cannot use that space.

Rules and Accreditation

Some outpatient surgery centers follow accreditation guidelines that recommend or require a BMI range, for example between 18.5 and 40. Surgeons who work there have to follow those rules, even if they personally feel comfortable operating on patients outside that range.

What the Research Says About BMI and Top Surgery

Across multiple studies of chest masculinization in transmasculine and nonbinary people, a clear pattern appears:

- Top surgery is safe for people across a wide range of BMIs.

- Most complications are minor and manageable.

- Serious, life threatening problems are rare, even in patients in the obese and morbidly obese BMI ranges.

Some studies look only at patients with BMI over 30, a group that is often excluded from surgery in real life. These studies still find that top surgery can be done safely, with outcomes that are comparable to those of thinner patients. In some cases, people with higher BMI do not have more complications at all, or the difference is small.

Larger studies that group patients by BMI do find that the chance of having any complication goes up in higher BMI ranges, especially at numbers like 40 or 50 and above. Even then, the overall risk of a serious complication stays low. This points toward managing risk through planning, support, and informed consent, rather than using BMI alone as a reason to deny or delay care.

What Risks Actually Go Up With Higher BMI?

When studies say that complications are more common at higher BMI, they are mostly describing a higher chance of problems that are uncomfortable, stressful, and sometimes need extra treatment, but are usually manageable.

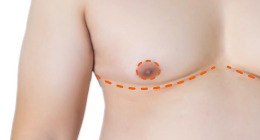

For top surgery, the most common risks across all body sizes include:

- Bleeding or bruising under the skin

- Fluid build up (seroma)

- Infection

- Delayed wound healing

- Scarring and contour irregularities

- Partial loss of nipple grafts in double incision surgery

At higher BMIs, some of these become a bit more likely. For example, several studies have found increased rates of wound healing problems or infections in patients with very high BMI, especially above 40 or 50. Even then, these are usually treated with antibiotics, dressings, or small in office procedures rather than major emergency surgery.

Anesthesia and Blood Clot Risk

Higher BMI can also interact with anesthesia and circulation. People with larger bodies are more likely to have:

- Sleep apnea or breathing issues

- High blood pressure or extra strain on the heart

- Reduced mobility, which can increase the risk of blood clots

These are real medical concerns, but they are also things a good surgical team can plan for. Screening for conditions like sleep apnea, adjusting anesthesia and positioning, using blood thinners when needed, and encouraging early movement after surgery can all help lower these risks.

The Need For Revision Or Extra Care

Some studies have found that patients with higher BMI may be a bit more likely to need extra support around surgery. That can include:

- Slightly longer time in the operating room

- More follow up visits

- Wound care over a longer period

- Revision surgery to adjust scars or chest contour

Healing can look different in larger bodies and may require more time and support. For most patients, the relief from chest dysphoria outweighs these risks.

Factors That Matter More Than BMI

BMI is only one small part of the picture. Other factors that can have a big impact on risk include:

- Smoking or nicotine use

- Uncontrolled diabetes or high blood pressure

- Blood clotting problems

- Heart or lung disease

- How active and mobile you are day to day

- How well supported you will be during recovery

Surgeons and anesthesia teams should be looking at all of these factors together, not just a single number. The real question is not “What is your BMI?” but “What does your overall health and support system look like, and how can we make this surgery as safe as possible for you?”

How BMI Cutoffs Harm Patients

Hard BMI limits are usually framed as safety measures, but they can cause real harm.

Being told you must lose weight before top surgery often turns into another form of weight stigma. People who are already pushed to the margins in healthcare, including fat and disabled patients and trans people of color, often face extra bias, and BMI rules add yet another barrier on top of that.

Delaying surgery to meet a BMI target can mean years more of binding and living with intense dysphoria. That delay can worsen anxiety and depression. When surgery is held out as a reward for weight loss, many people feel pushed toward crash dieting and disordered eating, which can be hard on both physical and mental health.

The evidence that BMI alone strongly predicts serious complications from top surgery is limited, while the intervention of prescribing weight loss carries real risks and a low chance of long term success. From an ethical standpoint, this is a serious problem.

Toward a Better Model

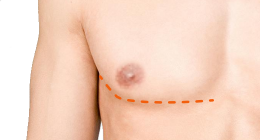

BMI can still play a role, but as a planning tool rather than a gate. A higher BMI might mean choosing a hospital OR, arranging closer follow up, or adjusting the surgical plan.

In a stronger informed consent model, your surgeon is upfront about what they know and do not know: how often complications happen in people around your BMI, what those problems usually look like, how they are treated, and what your surgeon has seen in similar bodies. You get clear facts and space to ask questions, and then you and your surgeon decide together whether the risk is acceptable.

Some surgeons are already using this approach, combining careful assessment of risk with honest conversations about tradeoffs, in their everyday practice. Dr. Laurel Chandler, a plastic and reconstructive surgeon in Connecticut who specializes in top surgery, describes it this way:

If I truly think someone is at high risk to undergo anesthesia I will let them know. I want all my patients to be safe to undergo surgery and optimal in terms of their overall health, but if someone has been dealing with dysphoria and has a difficult time losing weight I am not going to make them lose weight first.

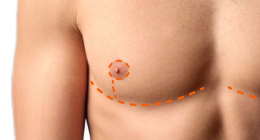

How Surgeons Use BMI Limits

BMI policies are not all the same. Depending on where you go, you might see:

- Surgeons who will not book a consultation above a certain BMI

- Surgeons who will meet with you, but will not schedule a surgery date until your BMI is below a specific number

- Surgeons who use BMI as a flexible guideline, looking at the full picture instead of treating it as a hard rule

- Surgeons who have no BMI limit at all and operate across the spectrum, sometimes moving very high BMI cases to a hospital OR for extra support

It can be hard to tell which situation you are dealing with.

Introducing the Top Surgery BMI Tracker

The Top Surgery BMI Tracker is meant to make part of this picture clearer. It gathers information about surgeons and the BMI numbers they use around top surgery into one searchable table. You can use it to check whether a surgeon lists a BMI limit for top surgery and to find surgeons who operate at higher BMIs or have no stated BMI limit.

In the table, a BMI value of 0 means the surgeon does not use a BMI cutoff. Some entries also note when the limit comes from the facility or accreditation rules, rather than the surgeon’s preference.

Policies can change, so it is always worth confirming directly with the clinic. Still, the tracker can save time and energy by helping you focus on surgeons who are better suited to your needs.

BMI is a single number pulled from a height and weight formula that reveals very little about an individual’s health, support system, or need for care. The research shows that top surgery is generally safe across a wide range of BMIs, with most complications being minor and manageable and serious events remaining rare. Higher BMI can raise some risks, but that calls for better planning and support, not a denial of care.

Hard BMI cutoffs ignore this evidence and place the burden on patients. They delay or block life changing surgery, worsen dysphoria and mental health, and push people toward unsafe weight loss attempts that are unlikely to succeed long term. From an ethical standpoint, it makes little sense to demand a risky, often ineffective intervention just to clear a barrier that is not well supported by the data.

After being denied a top surgery consult because of his BMI, Felix Vandergrift did not simply give up. He joined Gender Affirming Care Nova Scotia, a grassroots group that has worked with trans people across the Canadian province of Nova Scotia to create change. Their policy proposals focus on removing arbitrary barriers, including BMI-based restrictions, and expanding access to gender-affirming care in the public health system. Felix’s story shows how one person’s experience with such barriers can help drive real policy change.

Further Resources

- Questions to Ask at a Top Surgery Consultation About BMI

- Peer-Reviewed Studies About Top Surgery and BMI

Last updated: 11/14/25